Measurement

You can measure an audio device.

In fact there is a hell of a lot to be measured.

Does this tells you how it sounds?

The answer is no but measurements are not about are not about how a product sounds.

It is an analytical approach.

You want to hear the recording.

Every coloration added by the gear is unwanted as it is not the recording you are listening to.

Measurements tell you to what extend the gear is coloring the sound.

Measurements are by and large about what you don’t want to hear.

You don’t like to hear wow and flutter.

If the measurements tells you that the wow and flutter of a turntable are below audible threshold, you won’t hear it.

Likewise if a J-test (jitter test) of a DAC shows no skirting, no sideband and a extremely low noise floor, you won’t hear the jitter.

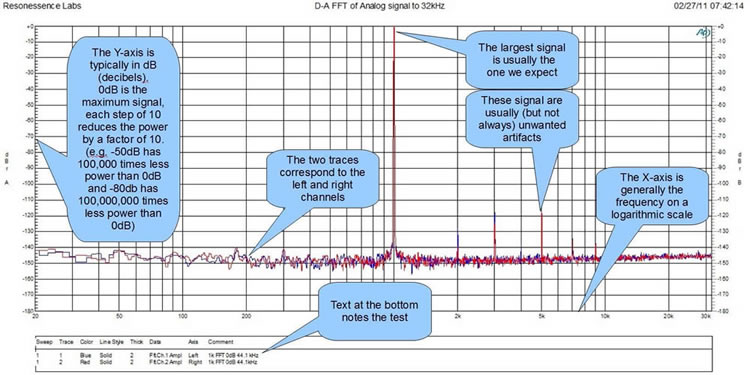

Jitter measurements

Often the Audio Precision audio analyzer is used to measure DACs.

The manual of Resonessence Labs Invicta DAC contains a short explanation (double click to enlarge).

Distortion

You can measure distortion.

If you can choose between two components, one with a higher and one with a lower level of distortion, what would you choose?

Sound like a rhetorical question, the one with the lowest distortion is of course the best. It does the least damage to the recording.

The funny thing is, a lot of audiophiles prefer analog.

Digital sounds too clean, is lacking warmth.

According to Hugh Robjohns the beloved analog warmth is a matter of distortion….

Fifty years of tape-machine design evolution reduced wow and flutter to extremely low levels by the 1980s, but it couldn’t be removed completely, and even the mighty Studer A820 two-track machine’s specifications quoted a wow and flutter figure of 0.04 percent when the tape was running at 15ips (inches per second). This is a tiny amount, certainly, but word-clock stability — which is the equivalent of wow and flutter in modern digital systems — can’t even be measured, as digital systems are orders of magnitude more stable in the time domain.

So what audible effect would such low levels of wow and flutter introduce? Well, the minute cyclical speed fluctuations of flutter, and particularly scrape-flutter, create subtle ‘side-bands’ and noise modulation around the recorded audio. These add a perceptible low-level ‘grunge’ to the sound, and while better-designed and maintained tape machines suffered lower levels of this grunge, it was always there to some extent. Although technically flutter is a fault, many argue that its side-bands and noise-modulation effects are an intrinsic part of the sound character of all analogue tape recordings, and that we’ve come to accept (and expect) them as part of recorded sound — and as part of what we call analogue warmth.